smoking

( Table 2).

However,

a

substantial

increase

in

e-

cigarette

smoking

in

a

short

period

has

been

reported

in

North American and European

countries. For

example, ever

e-cigarette use among students

in grades 6–12

in

the United

States

increased

from

3.3%

in

2011

to

11.9%

in

2013;

the

corresponding

increase

in

current

(past month)

e-cigarette

use was

from

1.1%

to

4.5%

[23] .Ever

use

of

e-cigarettes

in

the

French

population

aged

15

increased

from

7%

in

2012

to

18%

in

2013

[18].

In

2012,

1%

of

people

in

France

reported regular or occasional use of e-cigarettes

[13], but

in

2013,

6%

had

used

e-cigarettes

in

the

last

month

[18].

Similar

increases

have

likely

occurred

since

2012

in

many countries

in

the European Union,

in which a survey by

the

European

Commission

reported

that

the

prevalence

of

ever use of e-cigarettes varied

from 2%

in Sweden

to 14%

in

Belgium

[13].

One

of

the primary

concerns

of

e-cigarette use

is how

it

affects

cigarette use. E-cigarette use may not be

an

issue of

concern

if

it occurs only

in current smokers and only

if

it

led

to

smoking

cessation

or

at

least

a

substantial

decrease

in

smoking

intensity.

However,

e-cigarette

smoking

in

non-

smokers, or

in

current or

former

smokers,

that might

result

in

a maintenance

(with no

substantial decrease

in

smoking

intensity) or

surge

in

tobacco use

is

an

issue

that may need

preventive measures. Cigarette

smokers

should be

strongly

encouraged

to

quit

smoking

using

any

evidence-based

methods, with

or without

nicotine

replacement

therapy.

3.6.

Tobacco

control

policies

3.6.1.

MPOWER measures

Tobacco

control

policies

reduce

tobacco

use

and

related

harm.

Because

earlier

policies

usually

were

sporadic

and

isolated and could not prevent

the global

tobacco epidemic,

in

2003

the

World

Health

Assembly

adopted

the

WHO

Framework

Convention

on

Tobacco

Control

(WHO

FCTC),

the

first

international

treaty negotiated under

the

auspices

of WHO,

although

the WHO

FCTC

did

not

come

into

force

until

2005

[71].

In

2008,

WHO

identified

six

effective

evidence-based

measures

for

reducing

tobacco

use

and

began promoting

them under

the acronym MPOWER

[6].

In

2011,

UN member

states

committed

to

reduce

premature

mortality

from

noncommunicable

diseases

(a

25%

reduc-

tion

from

2010

levels

by

2025)

by

addressing

their major

risk

factors,

including a 30% relative reduction

in prevalence

of

current

tobacco

use

in

persons

15

yr

[72].

The worldwide

coverage

of MPOWER

policies

is

briefly

described

in

the

following

sections

and

is

summarized

in

Table 3(percentage

of

countries

with

coverage)

and

Supplementary

Table

2

(median

levels

of

coverage).

It

should

be

noted

that

tobacco

control

policies might

vary

within

countries

in

which

jurisdiction

is

subnational

for

some

policies

and/or

regulations.

In

the

United

States,

for

example,

the

northeastern

and

western

states

have

generally

been

more

successful

in

tobacco

control

than

the

southern

states

[53] .3.6.1.1. Monitoring

tobacco use and prevention policies.

Monitoring

tobacco

use

and

prevention

policies

is

necessary

to

assess

the

effectiveness

of

current

policies

and

the

need

for

any

policy modifications.

Tobacco monitoring

has

traditionally

been better

in countries with developed health surveillance

systems,

including Australia, Canada,

the United States, and

most

EU

member

states.

Broader

initiatives

such

as

the

Global

Tobacco

Surveillance

System

Surveys

[5],

which

provide

funding

and

training

from

high-income

countries

(notably

from

the US government and private

foundations),

can

help

improve

tobacco monitoring

in

LMICs.

3.6.1.2.

Protecting

people

from

tobacco

smoke.

As

exposure

to

secondhand smoke

is harmful

[73] ,smoking

in public places

has been banned

to some degree

in many countries.

In 2012,

however, only 16% of

the world’s population was covered by

comprehensive

smoke-free

laws

[6],

demonstrating

the

need

for

improved

implementation

and/or

enforcement

of

these

laws. Middle-income

countries

are

the

best

covered

with

smoke-free

policies,

with

South

America

being

the

leading

region

in

implementation

[6] .Smoking

in

cars

[74] ,outdoor

places

[75] ,and multiunit

buildings

[76]can also be sources of exposure to secondhand

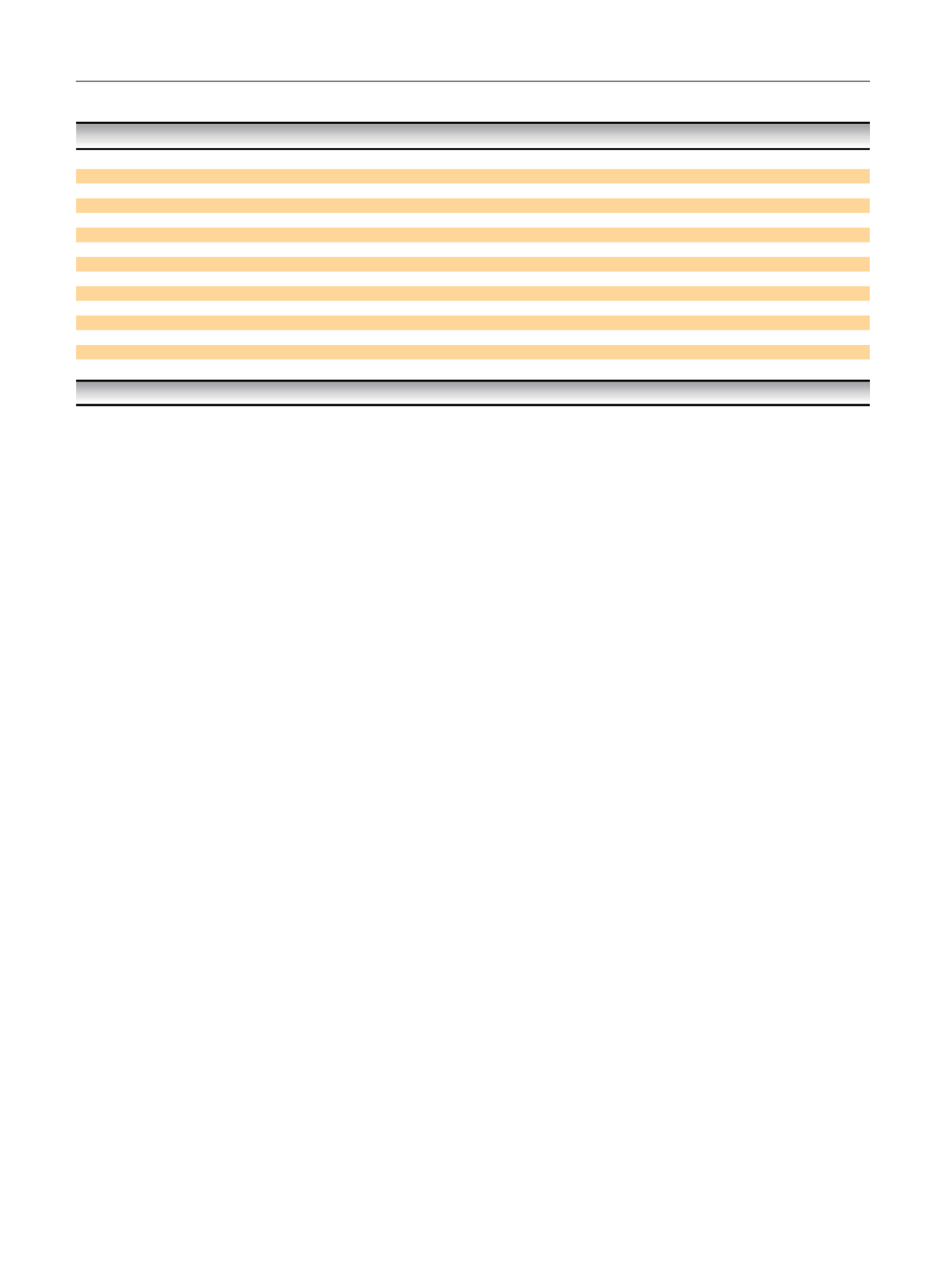

Table

2

–

Prevalence

of

e-cigarette

smoking

in

adults

and

youth.

Country

Year

Age

group

Ever

use,

%

Current

use,

%

Adults

Canada

[17]2012

16–30

yr

16.1

5.7

France

[18]2013

15

yr

18

6

Italy

[19]2013

15

yr

6.8

1.2

Spain

(Barcelona

only)

[7]2013–2014

16

yr

6.5

1.6

United

States

[8]2012–2013

18

yr

4.

2 a1.9

Youth

Canada

[17]2012

16–19

yr

12.5

2.6

France

[18]2013

15–24

yr

31

7

Poland

[20]2011

15–19

yr

23.5

8.2

South

Korea

[21]2011

School

grade

7–12

19.7

4.7

United

Kingdom

[22]2013

11–15

yr

4

1

16–18

yr

10

2

United

States

[23]2013

School

grade

6–8

3.0

1.1

School

grade

9–12

11.9

4.5

a

Every

day,

someday

,

or

rarely

users.

E U R O P E A N

U R O L O G Y

F O C U S

1

( 2 0 1 5

)

3 – 1 6

10