the

evidence

is

limited

and

results are

sometimes based on

experimental

or

in

vitro models

only

[11].

Constituents

of

cigarette

smoke,

such

as polycyclic

aromatic hydrocarbons

(PAH),

require metabolic

activation,

evasion

or

detoxifica-

tion

processes,

and

subsequent

binding

to

DNA

to

exert

their

carcinogenetic

action.

Consequently,

mutations

or

functional polymorphism

in genes

involved

in PAH metabo-

lism and detoxification may modify and

influence

the effect

of

smoking

on

PCa

pathogenesis

[50] .The

glutathione-S-

transferases (GSTs) comprise a class of enzymes that detoxify

tobacco-related

carcinogenesis

including PAHs by

conjugat-

ing

glutathione

to

facilitate

their

removal.

Of

the

seven

mammalian

GST

classes

characterized,

those

that

have

shown

substrate

specifically

for

PAH metabolites

and

that

are

expressed

in

the

human

prostate

include

GSTP

and

the

GSTM.

Human

prostatic

epithelium

predominantly

expresses

the GSTP1

subtype,

and

loss

of GSTP1

expression

has

been

observed

as

one

of

the

earliest

events

in

prostate

carcinogenesis

[51].

In

an

exploratory

case–control

study

evaluating

122

cases

of

PCa

and

122

controls,

among

participants with

the

genotype GSTP1

Ile/Ile,

smoking was

associated with

an

increased

risk

of

PCa with

an

adjusted

odds

ratio

(OR)

of 4.09

(95% CI, 1.25–13.35)

compared with

nonsmokers

[51].

GSTM

variants

have

also

been

shown

to

affect

the

association

between

smoking

and

PCa

risk.

In

a

family-based case–control design

study

(439 PCa cases and

479

brother

controls),

among white

participants

(90%

of

the

study

population),

heavy

smoking

increased

PCa

risk

nearly

twofold

in

those with

the GSTM1 null genotype

(OR:

1.73;

95%

CI,

0.99–3-05),

but

this

increased

risk was

not

observed

in

heavy

smokers

who

carried

the

GSTM1

nondeleted

allele

(OR: 0.95%; 95% CI, 0.53–1.71)

[50]. Mu-

tation

in

the

p53

gene,

one

of

the most mutated

tumor-

suppressor

genes

in

human

neoplasms,

or

in

the

human

cytochrome

P450,

which

is

involved

in

the

metabolic

pathways

of

several

endogenous

and

exogenous

com-

pounds

as

steroids

and

environmental

xenobiotics, may

play

a

significant

role

in modifying

PCa

risk

in

smokers

[52] .Increased

hemeoxygenase

1

(HO-1) messenger

RNA

expression

and

upregulated HO-1

protein

levels,

induced

by

smoking,

are

also

present

in

PCa

cell

lines

[53] .HO-1

may

have

a

role

in

tumor

angiogenesis

[54] .Exposure

to

carcinogenic

substances

found

in

cigarettes

(eg,

cadmium) has been

proposed

as

an

alternative mecha-

nism

for

PCa

carcinogenesis.

Cadmium

has

been

shown

to

indirectly

induce

prostate

carcinogenesis

through

interac-

tion with

the androgen

receptor. Ye et al

[55]have

reported

that cadmiumcan activate the androgen receptor response

in

human

PCa

cell

lines

in

the

absence

of

androgen

but

in

the

presence of

the

androgen

receptor. Cadmium also

enhances

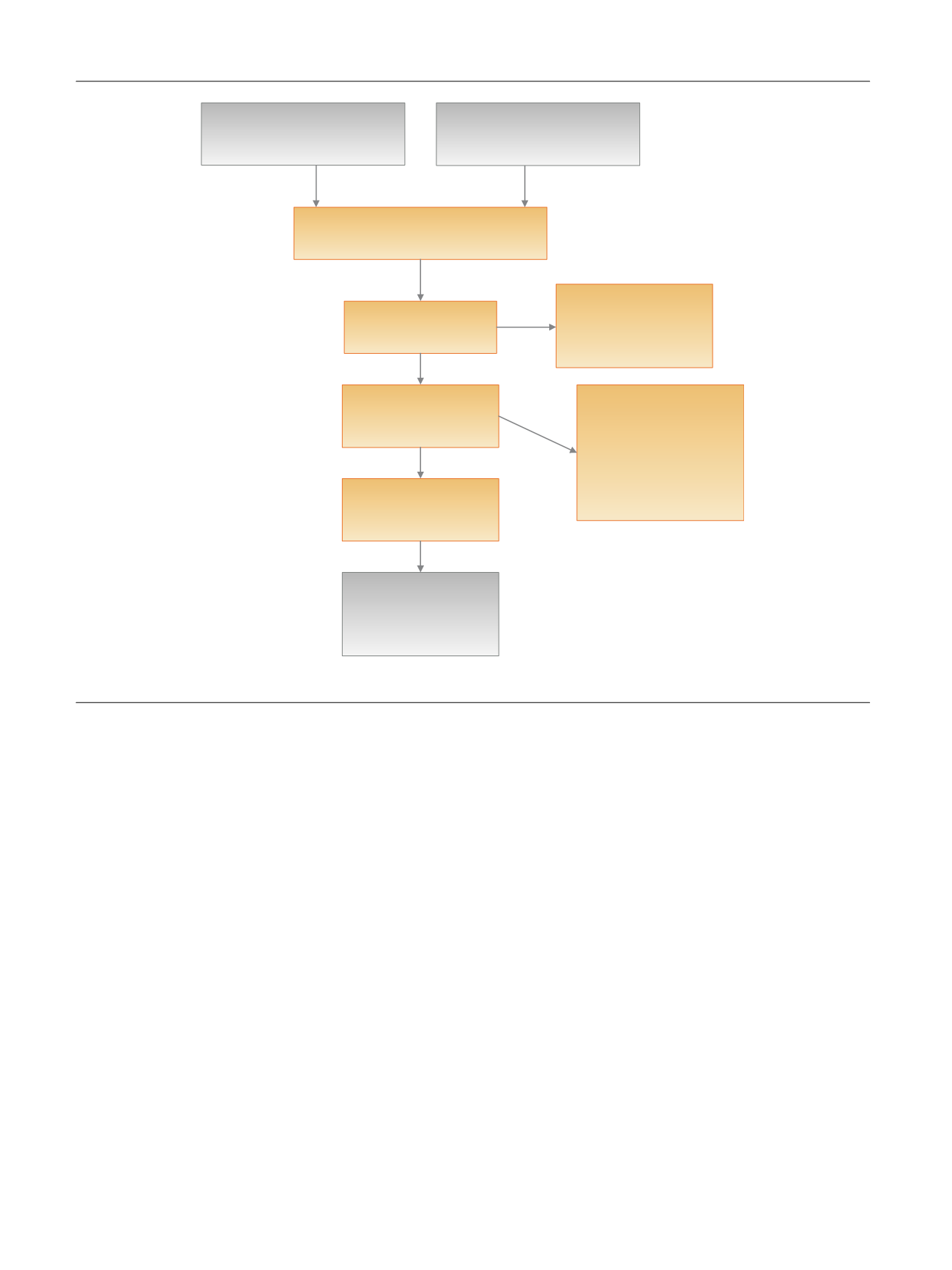

Records idenƟfied through

database searches

(

n

= 792)

AddiƟonal records idenƟfied

through other sources

(

n

= 10)

Records aŌer duplicates removed

(

n

= 554)

Records screened

(

n

= 248)

Records excluded because

they did not meet our

inclusion criteria

(

n

= 146)

Full-text arƟcles assessed

for eligibility

(

n

= 102)

Full-text arƟcles excluded

•

Similar or more

informaƟve data from the

same study were available

in another arƟcle (

n

= 25)

•

Not a systemaƟc review

(

n

= 9)

Studies included in

qualitaƟve synthesis

(

n

= 37)

Studies included as

addiƟonal references

(

n

=

31)

Fig.

1

–

Flow

diagram

of

the

search

results.

E U R O P E A N

U R O L O G Y

F O C U S

1

( 2 0 1 5

)

2 8 – 3 8

30