enriched with

FGFR3 mutations,

amplification,

and

expres-

sion

and

urothelial

differentiation

markers

(UPK1A,2,3A

and

KRT20).

Cluster

III

is

enriched

with

squamous

morphology,

basal

markers

(KRT

14,

KRT

5,

TP63),

and

expression of several

immune

response genes. We have also

performed unsupervised clustering of miRNA

in 310

tumors

and

provide

an

integrated

analysis

of

anticorrelation

of

clusters

of

miRNA

regulating

many

pathways

including

epithelial–mesenchymal

transition, DNA methylation,

and

FGFR3

expression,

among many

others.

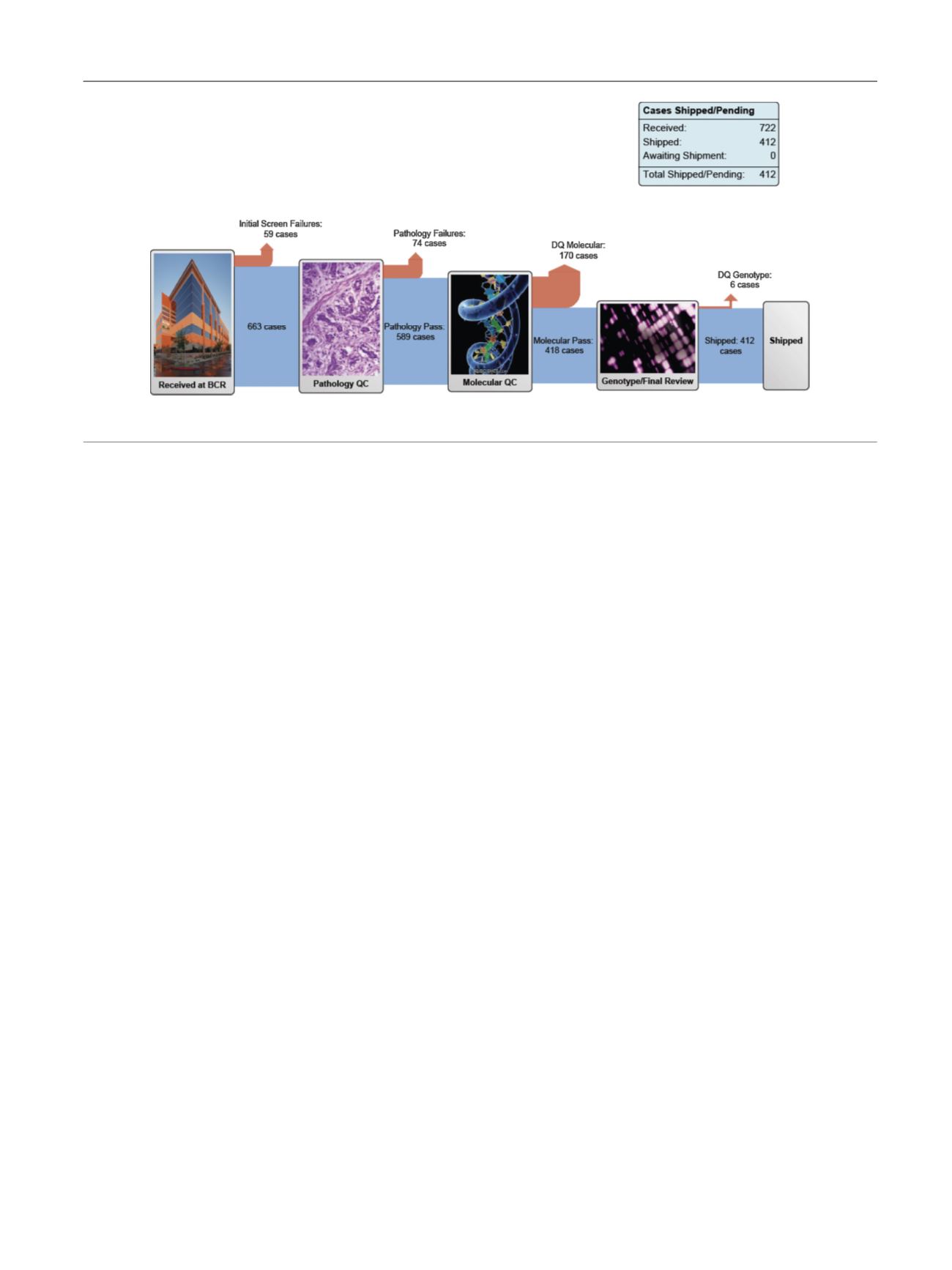

The

total

cohort now

includes 412

tumors

that have met

the

prespecified

quality

controls

for

pathology

and

RNA

quality

and

have

been

distributed

to

the

genome

charac-

terization

centers

[6] ( Fig. 1).

The

complete

data

set will

increase

the

power

to

detect

additional

low-frequency

events

[7],

validate

the

cluster

analyses,

test

hypotheses

regarding

chemotherapy

resistance,

and

provide

a

host

of

translational

opportunities

for

functional

validation

and

targeted

therapy

trials. Outcome analyses were deliberately

not

included

in

the

analysis

of

the

first

131

tumors,

as

the

follow-up

data were

not mature. We

expect

to

be

able

to

include

this

in

the

final

analysis

of

the

full

cohort.

The

analysis working

group

reconvened

in

early

2015

to

begin

the

final

analysis,

with

the

expectation

of

publishing

an

updated

comprehensive

integrated

analysis.

There

is

a

large unmet need

for

comprehensive genomic

characterization

of

non–muscle-invasive

bladder

cancer.

FGFR3

mutations

characterize

low-grade

Ta

tumors,

and

high-grade

tumors

share

similar

genomic

alterations with

muscle-invasive

carcinomas.

The National

Cancer

Institute

sponsored

a

clinical

trial

planning meeting

held

in March,

2015, with

one

of

the

goals

to

design

a

targeted

therapy

trial. A more

comprehensive understanding of

the genomic

landscape

is a critical step

in

this process. A recent

landmark

study

of

aristolochic

acid–induced

upper

tract

tumors,

using whole-exome

sequencing,

found

a

remarkably

high

somatic

mutation

rate

and

a

unique

mutation

signature

[8].

There

are

funding

opportunities

specifically

for

rare

cancers

(3–6

per

100

000),

and

this

presents

unique

collaborative

opportunities

for

important

research

on

the

biology

and

treatment

of

upper

tract

urothelial

carcinoma

[9].

Conflicts

of

interest:

The

author

has

nothing

to

disclose.

References

[1]

Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Comprehensive molecular characterization of urothelial bladder carcinoma. Nature 2014;507: 315–22.

[2]

Volkmer JP, Sahoo D, Chin RK, et al. Three differentiation states risk- stratify bladder cancer into distinct subtypes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2012;109:2078–83.[3]

HoPL,Kurtova A, ChanKS. Normal andneoplastic urothelial stemcells: getting to the root of the problem. Nat Rev Urol 2012;9:583–94.

[4]

Sjodahl G, Lauss M, Lovgren K, et al. A molecular taxonomy for urothelial carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res 2012;18:3377–86.

[5]

Hoadley KA, Yau C, Wolf DM, et al. Multiplatform analysis of 12 can- cer types reveals molecular classification within and across tissues of origin. Cell 2014;158:929–44.

[6]

BCR

pipeline

report.

The

Cancer

Genome

Atlas Web

site.

https:// tcga-data.nci.nih.gov/datareports/BCRPipelineReport.htm .Accessed

November

8,

2014.

[7]

Lawrence MS, Stojanov P, Mermel CH, et al. Discovery and saturation analysis of cancer genes across 21 tumour types. Nature 2014;505: 495–501.[8]

Hoang ML, Chen CH, Sidorenko VS, et al. Mutational signature of aristolochic acid exposure as revealed by whole-exome sequencing. Sci Transl Med 2013;5:197ra02.[9]

Participation

in Trials of Rare Cancers. National Cancer

Institute Web

site.

http://cancercenters.cancer.gov/news/news-announ-comm. html .Fig.

1

–

The

Cancer

Genome Atlas muscle-invasive

bladder

cancer

pipeline. Reproduced with

permission

from

the National

Cancer

Institute

[6].

E U R O P E A N

U R O L O G Y

F O C U S

1

( 2 0 1 5

)

9 4 – 9 5

95